All products featured on WIRED are independently selected by our editors. However, we may receive compensation from retailers and/or from purchases of products through these links.

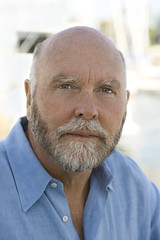

Four scientists - including the omnipresent J. Craig Venter (left) - have penned an opinion piece in the latest issue ofNature based results from five individuals genotyped by two separate personal genomics companies. The article highlights some deficiencies in the way that genetic data are currently used by direct-to-consumer companies to generate risk predictions and to present them to customers.

Four scientists - including the omnipresent J. Craig Venter (left) - have penned an opinion piece in the latest issue ofNature based results from five individuals genotyped by two separate personal genomics companies. The article highlights some deficiencies in the way that genetic data are currently used by direct-to-consumer companies to generate risk predictions and to present them to customers.

The identity of the tested individuals isn't made explicit in the article, except to note that there were two males and two females from the same family and one unrelated female. All of the individuals were tested by the companies 23andMe and Navigenics, which examine ~580,000 and ~923,000 sites of common genetic variation (SNPs), respectively. It's worth noting that in both cases the scans were performed before the companies were required to comply with CLIA standards (meaning that genotyping accuracy may have improved somewhat since these scans were done).The first result is reassuring: the concordance between the genotype calls from the companies was excellent, with disagreements at fewer than one in every 3,000 sites. Previous comparisons (see comments on this article) between 23andMe and deCODEme have found even smaller discrepancy rates, closer to one error in every 25,000 sites - the difference appears to be due to a substantially higher error rate on the Navigenics platform compared to 23andMe (compared to research-quality typing performed on the same samples, Navigenics had a 0.29% discordance compared to 0.01% for 23andMe). Overall, though, it's clear that the levels of technical accuracy being achieved by the genotyping platforms used by major personal genomics companies are perfectly acceptable.The real challenge is not with generating the raw genetic data, but rather with converting it into disease risk predictions - and here, the authors argue, the results of the comparison are less than ideal:> [We] found that only two-thirds of relative risk predictions qualitatively agree between 23andMe and Navigenics when averaged across our five individuals ... For four diseases, the predictions between the two companies completely agree for all individuals. In contrast, for seven diseases, 50% or less of the predictions agree between the two companies across the individuals.

The authors note that the discrepancies are primarily due to different criteria used by the companies to select risk markers. Coming up with robust and universal criteria for marker inclusion is something that was discussed in a meeting of the three major personal genomics companies back in July 2008. In a Bloomberg article today, 23andMe's Andro Hsu notes that the companies had "a pretty difficult time agreeing" on the criteria, and that uniform standards are "a great ideal, but difficult to implement in practice".It's worth noting that discrepancies between the predictions made by the companies don't necessarily mean that they are doing something wrong - predicting disease risk from genetic variants is still a new and uncertain field, and there is still plenty of room for valid disagreement on the best approach to use. However, I do agree that there are several areas where the companies could do substantially better, especially in terms of reporting the fraction of risk variance captured by their markers (more on this below).Venter and his co-authors make a number of recommendations targeted at personal genomics companies and the broader genetics community to improve risk predictions. I've listed these below, along with my comments:Companies should report the genetic contribution for the markers tested: personal genomics companies generally do a good job of explaining what proportion of disease risk is due to genetic vs environmental factors, but they typically don't spell out what proportion of the genetic disease risk is explained by the markers they test for. I agree with the authors that companies need to do a much better job of making this clear to customers; however, it's also worth acknowledging that this calculation is often non-trivial given the information currently provided in the published literature. This is as much an issue for the broader genetics community as for personal genomics companies.

Companies should focus on high-risk predictions: the authors argue that companies should "structure their communications with users around diseases and traits that have high-risk predictions"; basically, that they should focus heavily on the relatively small number of diseases for which an individual is at substantially above-average risk. This makes sense, so long as it doesn't come at the cost of reducing the availability of information to customers who actually do want to know everything.__

__Companies should directly genotype risk markers: it is common practice for companies to use nearby, tightly linked markers to "impute" the genotype for a risk marker not present on their chip. The authors note that while this works well on a population level, recombination can result in the new marker making incorrect predictions in a minority of individuals. I actually don't see this as a major issue: the published risk marker is almost never the actual causal variant, so no matter what you genotype it's likely that a non-trivial proportion of "at risk" individuals don't actually carry the true underlying risk variant; in fact, purely by chance, in many cases the marker chosen by the company may actually be a *better *proxy for risk than the published marker.Obviously once we have a catalogue of true causal variants we should ensure that those variants are present on genotyping chips; but until that occurs I don't have a major problem with companies using tightly linked proxies for risk prediction, so long as they are clearly marked as such.Companies should test pharmacogenomic markers: the authors argue that genetic variants predicting response to drugs will prove particularly useful. I agree, and so do personal genomics companies - given their utility and their interest for customers I have little doubt that these variants will generally be added to the companies' chips as soon as they become available.Companies should agree on strong-effect markers: several of the largest discrepancies found in this analysis were due to markers used by one company with relatively large predicted effects on risk that fell outside the criteria for inclusion for the other company. The authors suggest that companies need to agree on a core set of large-effect markers; that may prove challenging, but it would certainly be worth considering applying more stringent filters to markers with larger reported effect sizes in order to weed out markers with disproportionate effects of risk prediction.Finally, the authors make several recommendations to the genetics community. Two of these are very important: there needs to be a strong research focus on examining whether receiving genetic risk information actually changes behavioural outcomes, and on performing large prospective studies (that is, studies in which large numbers of people are genotyped and then followed to see if they develop common diseases) to validate risk prediction algorithms. Regarding the latter approach, the US government would do well to heed David Dooling's recent advice on the need for health care reform to enable such projects to move forward.The other two recommendations are actually both things that geneticists are already starting to do quite enthusiastically: replicating risk variants in other populations, and using sequencing-based rather than genotyping-based approaches. In summary: it will be very interesting to see whether this high-profile publication provokes personal genomics companies into tightening up some aspects of their reporting. However, in my view the best thing about this article is that it demonstrates scientists actually engaging constructively with the personal genomics industry rather than jeering derisively from the sidelines (something I've seen all too frequently in recent conference presentations). This sort of engagement is critical if the genetics community wants to influence the way that personalised medicine evolves over the next few years. ![]() Subscribe to Genetic Future.

Subscribe to Genetic Future. ![]() Follow Daniel on Twitter.

Follow Daniel on Twitter.